Research

Mobile Urban Sensing System

Healthcare Supply Chain Automation

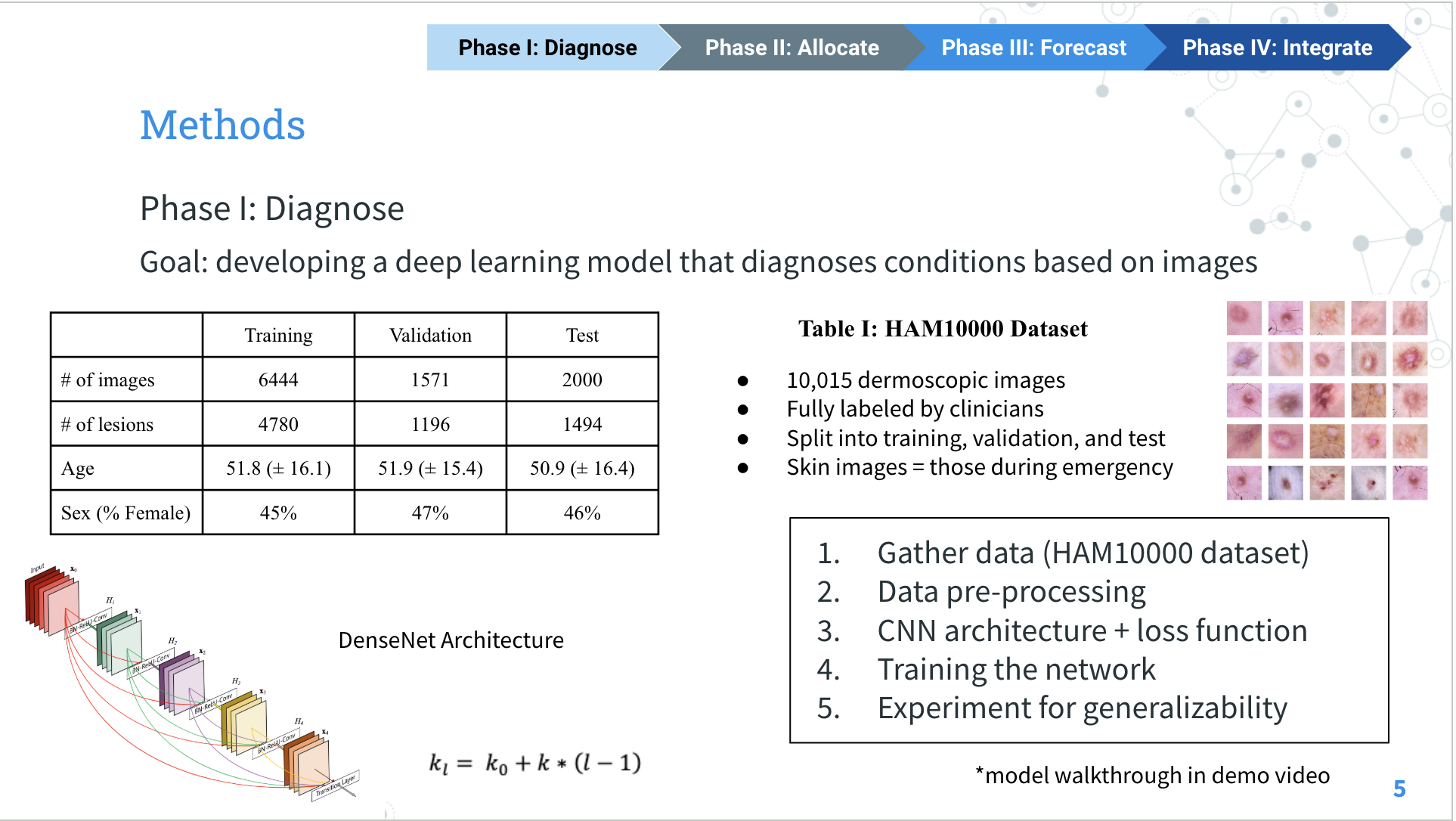

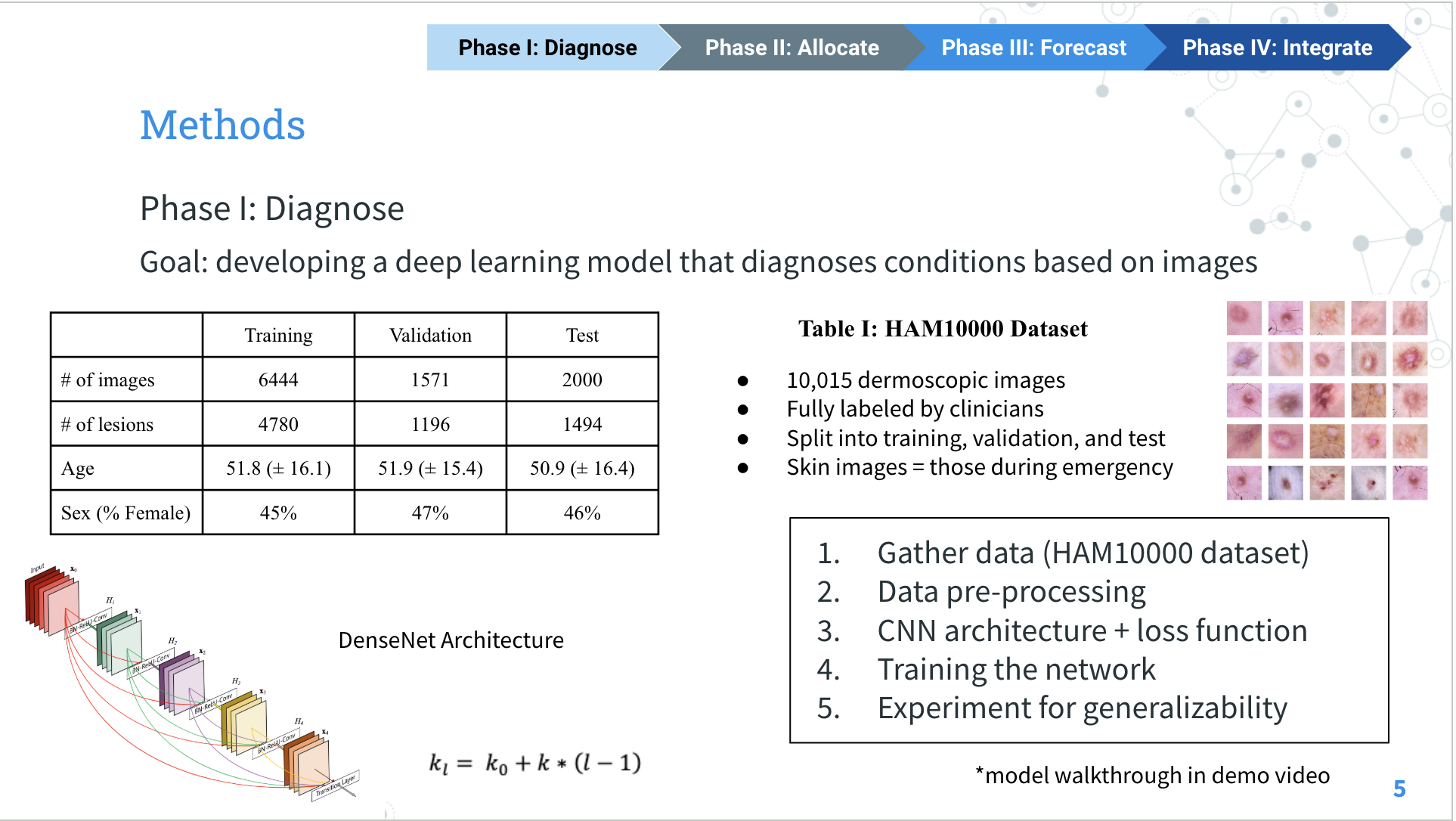

An Integrated Deep Learning Platform to Optimize and Forecast Surgical Supply Demand

As a part of Cornell DEBUT, I have been a part of designing a cane with a built-in tuned-mass damper intended to effectively dampen hand tremors. The prototype comprises of two main characteristics: a spring-based, two-degree freedom damper, in addition to a specially 3D-printed base for increased surface contact during gait.

The assembly of our design began with a CAD to model the cane with the TPU base and the Tuned Mass Dampening system. The cane’s base consists of a 3-D printed upside-down bosu ball shape made of TPU filament. The bosu ball concept prioritized stability with flexibility: we took the CAD a step further to create treads at the bottom of the bosu ball, preventing slippages at different angles. We coated the bosu ball with plasti-dip to generate more traction with the points of contact. The nuts and bolts with the specific dimension of the 3-D printed base were inserted as shown on the CAD along with the support bolts to attach the base to the cane.

We approached the testing portion of the cane in two different ways to maximize our data. Initially, we created a testing rig that aimed to simulate a Parkinsonian tremor. Through an upside-down mechanism via wooden dowels, string, and bolts, we secured the main TMD component hanging from a PVC pipe representing a dummy hand. We attempted to replicate the tremor through utilizing Cornell Seismic Design Project Team’s shake table, aligning with our original concept of tuned mass dampening during earthquakes. However, we found that our human-made rig could not account for all the aspects of a Parkinsonian tremor, from the movement of the arm to the uncontrolled duration. Due to the confounding factors, we wanted to test the product in a low-risk environment with Parkinsons patients. Our team sought out IRB approval and, after a lengthy process, we were approved to test the cane on Parkinsons patients in Dr. Bauer’s lab at SUNY Cortland.

Prior to the day of testing, we prepped all necessary consent forms, QUEST questionnaires, and data protection measures. The testing protocol, as approved by Cornell’s IRB committee, involved a series of tasks that our team walked the patients through. In the morning, our team split up into two groups, one with each patient and either the standard or the experimental cane. While the first group ran the patient through the 7 trials with the standard cane, the other group did the same with the other patient and the experimental cane. With thorough review from prior Parkinsons mobility research, our trials consisted of a baseline tremor, walking in a straight line, walking with a right turn, walking with a left turn, walking up and down a short staircase, and sitting back down in a chair. The same two groups ran the same procedure with two more patients in the afternoon. As the patients conducted the trials, we collected data through the accelerometer attached on their hand. We gathered their insights and feedback on the standard vs. experimental cane and learned from their experiences living with a Parkinsonian tremor. All data is protected via IRB-approved security measures on Box.

Our team acquired over 80,000 data points, consisting of the x, y, and z accelerometer values from the experimental and control cane for each patient. In post-processing, the data was filtered and fitted with a spline with a MATLAB script that additionally averaged the max peak value of the spline. To compare the experimental to the control group, the deviation from the base tremor recorded at the start of each experiment is computed to create a percentage change. Each average peak value in addition to the percentage deviation from the base tremor is charted in our results.

Analyzing human liver carcinoma datasets for epigenetic patterns through spatial transcriptomics. Accelerating bioinformatics tool development with lab’s PhD students.

Launched a project to bridge translational loopholes between AI and clinical workflows within radiology. Interviewing head neuroradiologists at Weill Cornell, Stanford, etc. Facilitated research on ordinal regression models for Alzheimer’s diagnosis and prognosis.

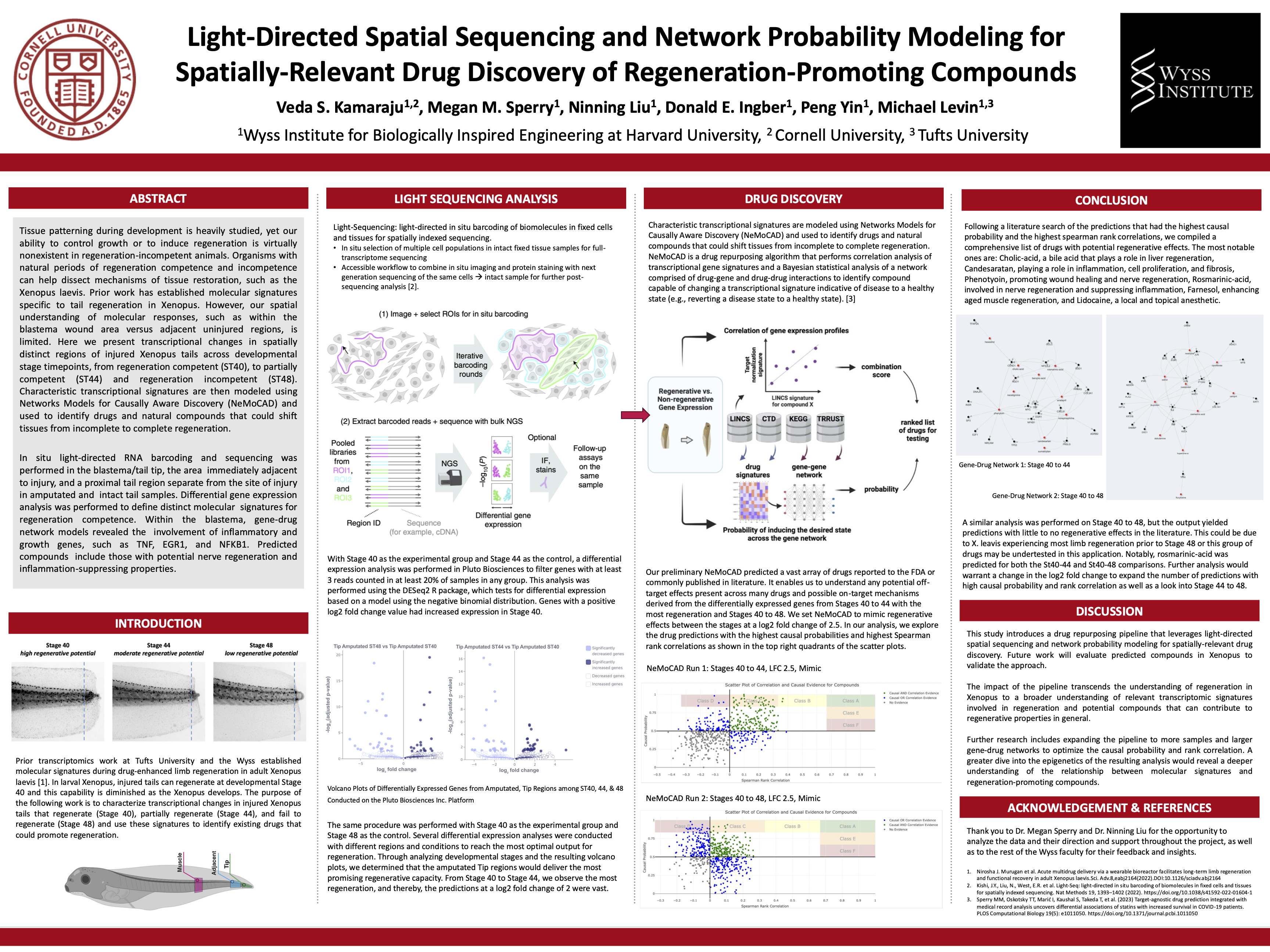

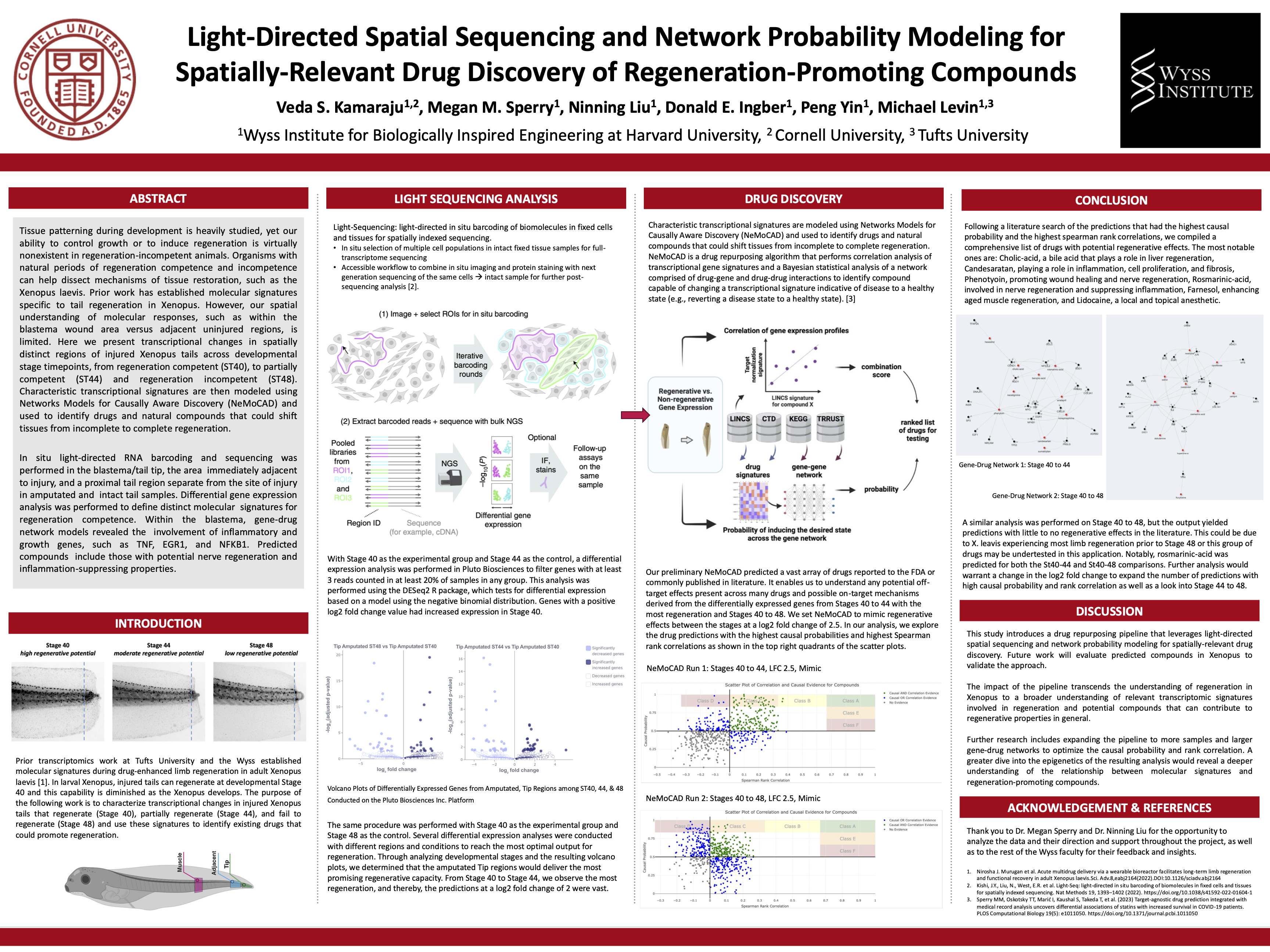

Curated a pipeline for the optimal use of Graph Neural Networks. Leveraged NVIDIA open-source software to create a bare-bones LLM to facilitate drug repurposing. Prepared material to NVIDIA representatives for usage of BioNeMo at the Wyss. Analyzed biological and genetic pathways in anesthesia-induced Xenopus models under a Department of Defense grant and in-situ light-directed spatial sequencing data via R and Python. Modeled drug-gene neighborhoods through a probabilistic network algorithm for drug repurposing and discovery. Presented poster at the 2025 Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering Conference.

The goal of the project would be to create a mobile urban sensing platform that provides the users with instant air quality measurements of CO, NO2, NH3, etc. percentages, tracks relations of air quality with diseases like asthma, respiratory disease in neighborhood, provide air quality indicators in the form of red, green, and orange to alert the users, and provide users with recommendations to deal with the current poor air quality.

The system was capable of detecting and analyzing air pollutants, as well as producing AQI levels accordingly. It successfully offered proper recommendations based on the AQI levels in pursuit of preventing the dangers of air pollution. Further testing in polluted areas, such as Butte County, will effectuate improvements in the system. I envision my Mobile Urban Sensing System on the wrists of civilians, integrated with location hotspots of the mobile devices hinged onto vehicles or bikes, and collaborated with transportation options, such as Uber or Lyft, in urban cities.